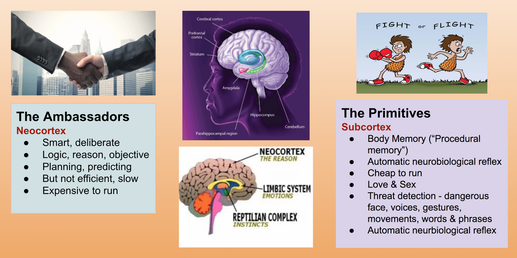

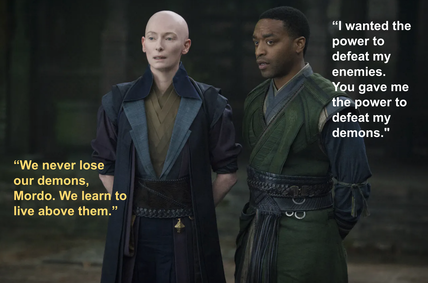

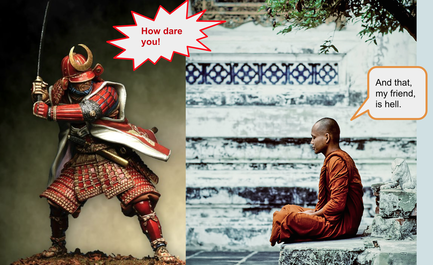

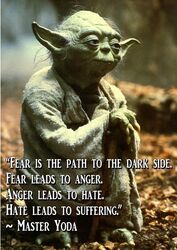

The synoptic gospels tell the story of very scared and anxious disciples on the boat pounded by a storm. After the disciples express their fear of drowning, Jesus says, “Peace be still,” then calms the seas. He invites them to have faith and not be afraid. In the middle of the stormy seas, Jesus found peace and invites his disciples to do so. Likewise, the Buddha invites his followers to find stillness in the eye of the storm (samsara) amidst our chronic and vain attachment to things shallow, superficial, impermanent and ever-changing. We seek deep peace in our lives and yet our instincts to hook on to our anxiety, worry, anger, and fear seem to constantly follow us wherever we go. Its ugly head rears itself without warning. We wish we have control over our anxiety and fears, but our automatic threat response system seem to be a bit more wiley than we wish it to be. And before we are even aware of it, the automatic threat response system has taken over the driver’s seat. The Subcortex  In his book, Wired for Love, couples therapist Stan Tatkin talks in detail the researched data from neuroscience about the dynamic between the brain’s prefrontal cortex and the subcortex. He calls the former, the “ambassadors” - the part of our brain that specializes rational thinking. He calls the latter “the primitives” - which is the home of our automatic threat response system. In general, our brains lean towards negative bias (1 to 5 ratio of positive to negative), it has an extremely efficient tracking system for potential threats. The amygdala in our subcortex for instance exists to do what it was designed to do over thousands and thousands of years - to help us survive from life-threatening attacks from predators. In a way, we literally have a kind of a reptilian instinct within us. This is our dragon. This raw animal instinct in us has come up in our mythology, our sacred stories, usually in the form of an actual animal (snake) or a giant reptile with wings that breaths fire (dragon), or someone that is part human and part animal (centaur, minataur). Or perhaps a human figure with horns of a ram with bat-like wings (devil)? Mythology Our human struggle with the dragon within ourselves is well recorded in human mythology. Scholar of mythology Joseph Campbell explains that the dragon from the East and the dragon from the West have differences. Personified in the story of St. Michael and the dragon, the western dragon, Campbell says, is to be killed so that the hero(ine) can access the treasure that the dragon protected in its lair. The dragon represents our ego, and our attachment to it. In western mythology, the ego has to die in order for resurrection to a life that is free from the shackles of self-centeredness.  The eastern dragon, on the other hand, is different from its western counterpart. The Chinese dragon, for instance, is not necessarily an enemy to be defeated and killed. This dragon however is still dangerous and wild, much like it’s western equivalent. But this dragon represents vitality - it dances, it beats its chest and laughs a big belly laugh. This dragon invites the hero(ine) to participate in the dragon dance. A few times in San Francisco’s Chinatown, I have seen youth who take Chinese martial arts, take on the dragon costume to do the dragon dance. Below are some mythologies - both contemporary pop culture and ancient - on the human struggle to tame the dragon within. Bruce Lee, the Dragon Fans of Chinese Kung Fu films know that Bruce Lee, the martial arts hero, is identified as the dragon. He was an athlete who immersed himself in eastern philosophy which he integrated in his physical discipline. Lee fully understood that in order to become an adept athlete (which in his case is as a martial artist), he had to be aware that ultimately the demon that he has to fight with is not his opponent in front of him. The demon (the dragon) is within oneself: the attachment to one's thoughts and ego, unable to see "what is" in the here and now. In this clip from the blockbuster film Enter the Dragon, Lee engages a philosophical conversation with an old and wise shaolin monk about the value of engaging the martial arts discipline without the interference of the ego.  The Ancient One (in Marvel's Dr. Strange) The Marvel film, Dr. Strange, also highlights the eastern mythology of the dragon within ourselves through a conversation between the master (the Ancient One) and the student (Karl Mordo). Karl Mordo (disciple): “I wanted the power to defeat my enemies. You gave me the power to defeat my demons." Ancient One (master): “We never lose our demons, Mordo. We learn to live above them.” The Ancient One points out to the student (Karl Mordo) that overcoming the one’s demon does not mean eliminating (or losing) it for it is an inextricable part of who we are, so much so that we are hardly aware of it when it acts out through it's lighting speed automatic threat response, or when it narcissistically pumps itself up by stubbornly defending its self-righteousness. Learning to live "above them" is a skill. Stan Tatkin explains that observing our demon-dragon (our primitives) in action helps to keep them in check. By developing disciplined self-awareness, we can observe how they behave, and begin experimenting if we can catch them in the act. We can develop and refine this skill over a lifetime - but not without help.  The Samurai and the Monk (plus Yoda) For this reason, having a mentor or teacher is part of Eastern spiritual traditions as illustrated in the stories from Enter the Dragon and Dr. Strange. The Zen story about the samurai and the monk focuses on the role of the teacher as the one who guides the student to "awaken" from the self-centered habitual thought patterns of the ego. After a warrior returning home from war crosses paths with a wise meditating monk, the warrior asks the monk: “Explain to me the truth about heaven and hell.” The monk tells the samurai that this was not possible since the warrior was “dumb and ugly.” With his anger triggered, the samurai drew his sword ready to chop the head of the monk. Then the monk says, “And that my dear friend is hell.” The samurai awakens to the teaching of the wise monk. With the insight he had gained, he lays down his sword, and bows to the monk in deep gratitude. The monk then says, “And that my friend is heaven.” In this story, the monk helped the samurai catch his dragon in the act by inviting him to become the awareness or observer of his reaction which was in the process of turning from a small spark into a violent explosion.  The monk taught the samurai awareness of his dragon by poking the samurai's fragile ego. It's very likely that in his earlier life he was bullied and called dumb and ugly. While he might have been an accomplished and respected samurai, he carries with him unhealed inner scars from his past, and continues to suffer each time his unhealed scar is touched. A common wisdom in psychology states that anger at its deepest level is rooted in fear. Anger is a powerful energy that can be utilized to address injustice when our human rights are disregarded. But if we hold on to it like a barnacle, it has the potential to harm us. A small spark mixed with very volatile fuel of hate can cause death and destruction. The Jedi Master Yoda from the Star Wars mythology holds this assumption when he reminds the young padawan: "Fear is the path to the dark side. Fear leads to anger. Anger leads to hate. Hate leads to suffering." In Star Wars, the young Anakin Skywalker succumbs to his dragon and becomes Darth Vader.  Avatar the Last Airbender In the episode entitled “Firebending Masters” of the anime series Avatar the Last Airbender, the two characters Aang and Zuko give us some ideas how not to be paralyzed by our fears. When both confront the two ancient dragons to learn the secrets of firebending, the audience is held for a few moments of the possibility of the two teens being eaten by the dragons. While facing danger, Aang realize that in order to build rapport with the dragons, he and Zuko have to do the dragon dance. As soon as both perform the dance, the wild dragons dance with them harmoniously and gracefully, an act which imbue the two students with the wisdom and beauty of firebending. Both discover that learning the nature of fire merely through one's anger is not enough to sustain healthy resilience in the long-term. Anger - the fire that destroys - has a short life. In the end, they learn the life-giving nature of fire (sun), which sustains life on earth.  Sun-Girl & Dragon-Prince (Armenian Mythology) While stories of humans taming dragons dominates in Eastern mythology, this archetype takes place in Western mythology as well. In an Armenian story, "Sun-Girl and Dragon-Prince," a girl by the name of Arevhat is about to be fed to the Dragon-Prince, but instead of being overcome by fear, she greets him warmly, "Good evening, King's son." The dragon is moved by her presence and empathy that the tears that roll from his eyes melt the scales in his body tranforming him into a full human. Much like the Zen story of the monk and the samurai, this story illustrates how awareness, presence and empathy has the power to tame the violent dragon impulse within ourselves.  Eustace Scrubb Becomes A Dragon (Chronicles of Narnia) In C.S. Lewis' "Voyage of the Dawn Treader," eleven year old Eustace Scrubb begins as an arrogant self-absorbed boy, until he, unbenownst to him, becomes a dragon while on an adventure with his cousins. At some point, he realizes that the dragon that he sees in the pool is his own reflection. He begins to see something about himself that he has not been fully aware before: his "greedy dragonish thoughts in his heart." As a dragon, he tries to embody new behaviors by helping his fellow travellers find food and shelter. Eventually, the great lion Aslan helps him peel off his dragon skin and throws him into a body of water. When he emerges he becomes himself again, but is also transformed into new person that others around him can truly befriend. In order for Eustance to free himself from his dragon tendencies and impulses, he has to fully accept that the dragon is a part of who he is and find some self-awareness of the ways of the dragon. Only then can he allow space within himself to embody kindness, compassion, and true friendship with others. Where the Wild Things Are  Author and illustrator of children's books, Maurice Sendak, also plays with the theme of taming monsters. In the Wild Things Are, Max confronts his monsters as they "roared their terrible roars and gnashed their terrible teeth and rolled their terrible eyes and showed their terrible claws." With the magic trick, he tames them and dances with them. This story points at the notion that often that which we perceive as threatening is often not as dangerous as we think it is. Writer of children’s books, Kathy Hoopman, writes in All Birds Have Anxiety: “The amazing thing is when you force yourself to face what scares you, or you start whatever it is you are worried about, the scariness shrinks….Then you will find that the things you thought would be terrible have no real terror in them, and things you thought would be horrible are not full of horror.”

Jesus' Temptation In the synoptic gospels, Jesus struggles with his dragon, which comes to visit him in the form of devil in the temptation scene in the wilderness. The devil offers him the values of self-centeredness: power (turning stone to bread), control (kingdoms) and permanence (avoid death). Jesus rejects these offers when devil visits him in the desert. Jesus overcomes his automatic threat response system by responding to God's call towards altruism, love and empathy. In closing, increasing our self-awareness will help make the dragon within us become more visible. Learning to tame and dance with our dragons is something we can develop and refine, but this will not happen overnight. It is a learning process that will take place over a lifetime, and not without help. |

Donnel Miller-MutiaJoin me in chewing the cud on mindful communication and relationships, self-awareness, spirituality and mythology. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed