INTRODUCTION

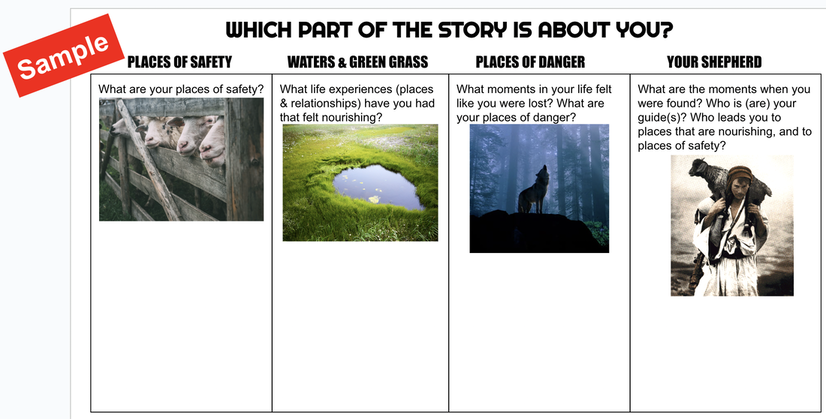

We constantly journey through our highs and lows: between moments of safety and nourishment, and moments of danger. While the Parable of the Good Shepherd leans towards giving hope to those who feel lost in places of danger, there are participants in the support groups that I facilitate who claim that no one has come back to find them. They feel that they are still in danger and have not found their places of safety. They feel hopeless and disappointed.

The impulse to preach and give false hope by making predictions as offered by the parable is tempting (i.e., you will be found). However, the role of the chaplain is simply to bear witness to how the sojourner finds oneself in the terrain or map of the never-ending flux of the highs and lows, and then invite the listener of the parable to wonder and to notice: to name one's experience as it is using the mythological archetype as a lens.

We feel disempowered when our experience of disorientation remains unnamed and nameless. But naming one's experience of disorientation is a powerful act.

We constantly journey through our highs and lows: between moments of safety and nourishment, and moments of danger. While the Parable of the Good Shepherd leans towards giving hope to those who feel lost in places of danger, there are participants in the support groups that I facilitate who claim that no one has come back to find them. They feel that they are still in danger and have not found their places of safety. They feel hopeless and disappointed.

The impulse to preach and give false hope by making predictions as offered by the parable is tempting (i.e., you will be found). However, the role of the chaplain is simply to bear witness to how the sojourner finds oneself in the terrain or map of the never-ending flux of the highs and lows, and then invite the listener of the parable to wonder and to notice: to name one's experience as it is using the mythological archetype as a lens.

We feel disempowered when our experience of disorientation remains unnamed and nameless. But naming one's experience of disorientation is a powerful act.

|

The Parable of the Good Shepherd

(from Godly Play® storytelling - see Godly Play® links to purchase storytelling materials, and to learn about the Godly Play® approach, and how to receive training.) There was once someone who said such amazing things and did such wonderful things that people followed him. They couldn’t help it. They wanted to know who he was, so they just had to ask him. Once when they asked him who he was, he said, “I am the Good Shepherd. I know each one of the sheep by name. When I take them from the sheepfold they follow me. I walk in front of the sheep to show them the way. “I show them the way to the good grass and I show them the way to the cool, still, fresh water. When there are places of danger I show them how to go through." “I count each one of the sheep when they come back and go inside the sheepfold. If one of the sheep is missing I would go anywhere to look for the lost sheep—in the grass, by the water, even in places of danger." “And when the lost sheep is found I would put it on my back, even if it is heavy, and carry it back safely to the sheepfold. “When all the sheep are safe inside I am so happy that I can’t be happy just by myself, so I invite all of my friends and we have a great feast.” Now this is the ordinary shepherd. When the ordinary shepherd takes the sheep from the sheepfold, he doesn’t always show them the way, and so they wander. When the wolf comes, the ordinary shepherd runs away. But the Good Shepherd stays between the wolf and the sheep. The Good Shepherd would even give his life for the sheep, so they can come back safely to the sheepfold. |

|

Guide for Facilitators of Spiritual Care Support Groups

Practice the Godly Play storytelling: