INTRODUCTION

As an artist I have always been drawn to the Japanese aesthetics of wabi-sabi. When my family moved to the southwest and had our own yard for the first time (something we could not afford in California), I immediately experimented with this creative approach when I designed my xeriscape yard using various types of rocks.

In this philosophy, one assumes that there is something lifegiving around the old, rustic and imperfect. When I delved into the grief support world in my work as bereavement coordinator in hospice, it was no surprise to me that therapists used the wabi-sabi philosophy as represented in the art of kintsugi. Negative space, cracks, holes, shadows, tension, imbalance and movement are more valuable than positive space, the new, light and symmetry and balance.

This aesthetic preference shows up in Christianity; however, it is not focused on things but on humans. Jesus as a healer did not affiliate with the "perfect" (rich and powerful); Jesus shows up with the poor, the sick, the hungry, with the least of these - in other words, Jesus always gave preferential option for the rustic parts: the wabi-sabi of human life and experience.

As an artist I have always been drawn to the Japanese aesthetics of wabi-sabi. When my family moved to the southwest and had our own yard for the first time (something we could not afford in California), I immediately experimented with this creative approach when I designed my xeriscape yard using various types of rocks.

In this philosophy, one assumes that there is something lifegiving around the old, rustic and imperfect. When I delved into the grief support world in my work as bereavement coordinator in hospice, it was no surprise to me that therapists used the wabi-sabi philosophy as represented in the art of kintsugi. Negative space, cracks, holes, shadows, tension, imbalance and movement are more valuable than positive space, the new, light and symmetry and balance.

This aesthetic preference shows up in Christianity; however, it is not focused on things but on humans. Jesus as a healer did not affiliate with the "perfect" (rich and powerful); Jesus shows up with the poor, the sick, the hungry, with the least of these - in other words, Jesus always gave preferential option for the rustic parts: the wabi-sabi of human life and experience.

Kintsugi

During the 15th century Japan, there was a shogun by the name of Ashigaka Yoshimasa who was fond of collecting art and surrounded himself with artists and poets in his temple palace Ginkaku-ji.

Yoshimasa loved tea ceremonies, which in their culture was a sacred event; the tea ceremony gave the participant the opportunity to become enlightened (an experience of awakening into truth and wisdom).

During these tea ceremonies, Yoshimasa always used his most precious tea bowl, but unfortunately, one day an accident happened - the bowl fell and broke into pieces.

The broken tea bowl was immediately sent back to the skillful Chinese ceramist in China where it came from.

The Chinese ceramist repaired it with their standard process of fixing the broken parts with iron staples. Yoshimasa was extremely disappointed with the results of the aesthetic look - he found the mending of the bowl with metal staples unsightly.

During the 15th century Japan, there was a shogun by the name of Ashigaka Yoshimasa who was fond of collecting art and surrounded himself with artists and poets in his temple palace Ginkaku-ji.

Yoshimasa loved tea ceremonies, which in their culture was a sacred event; the tea ceremony gave the participant the opportunity to become enlightened (an experience of awakening into truth and wisdom).

During these tea ceremonies, Yoshimasa always used his most precious tea bowl, but unfortunately, one day an accident happened - the bowl fell and broke into pieces.

The broken tea bowl was immediately sent back to the skillful Chinese ceramist in China where it came from.

The Chinese ceramist repaired it with their standard process of fixing the broken parts with iron staples. Yoshimasa was extremely disappointed with the results of the aesthetic look - he found the mending of the bowl with metal staples unsightly.

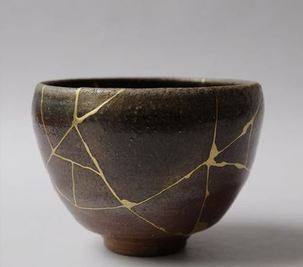

For this reason the bowl was then given to the Japanese craftsmen to find a better and more beautiful solution, and this motivated them to find an alternative, aesthetically pleasing method of repair.

The cracked pieces are sealed together with gold. Namely, the practice is related to the Japanese philosophy of wabi-sabi, which emphasizes the thought of finding beauty in every aspect of imperfection in nature and embraces the “imperfect, impermanent and incomplete.” Thus kintsugi calls for seeing beauty in broken things.

Yoshimasa not only praised the uniquely mended bowl but also loved to see how it has been given a new life with its imperfections that are now full of beauty.

The cracked pieces are sealed together with gold. Namely, the practice is related to the Japanese philosophy of wabi-sabi, which emphasizes the thought of finding beauty in every aspect of imperfection in nature and embraces the “imperfect, impermanent and incomplete.” Thus kintsugi calls for seeing beauty in broken things.

Yoshimasa not only praised the uniquely mended bowl but also loved to see how it has been given a new life with its imperfections that are now full of beauty.

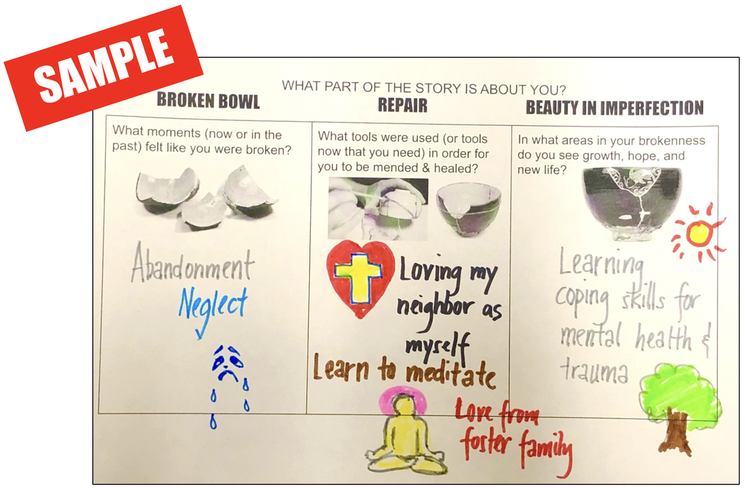

REFLECTION QUESTIONS

- What did you find to be the most important part of the story? What resonated with you?

- What experiences have you had that is close to this story?

- Where do you find yourself in this story? Which part of the story is about you?

Guide for Facilitators of Spiritual Care Groups

Practice Spirit Play storytelling:

- STORY MATERIALS

- VIDEO

- SCRIPT