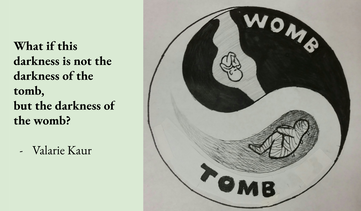

After getting hired as a chaplain for BH patients about three years ago and noting that there were no readily available curriculums in the chaplaincy world for spiritual care support groups, I immediately knew the approach I was going to use: Godly Play (or Spirit Play). For many years I have accompanied all of my three kids for Godly Play at our church, with me mostly serving as a “Godly Play door person” and keenly observing diverse facilitation styles of the trained Godly Play teachers. I have seen the effectiveness of the pedagogy grounded on Montessori theoretical frameworks which was very inclusive to different types of participants (age and mental capacity). While the Godly Play approach was sound, the only problem was that the selection of stories were limited by Judeo-Christian mythological narratives, which was limiting for my context as a chaplain in a secular hospital. However, looking for stories beyond the Judeo-Christian framework was right up my alley. In college, I was a Religious Studies major exposed to the diverse mythologies of cultures around the world. Early on, through the work of Joseph Campbell (influenced by Carl Jung), I was hooked on the universal archetypes. On top of being a world mythology geek, I have learned the significance of music after working with dementia patients. As also know the value of visual arts after serving as an art teacher and organizer of a summer arts camp program for inner city youth. With inclusivity as the main goal of my Spiritual Care Support Group sessions, I want to highlight in this blog why music, art and Godly Play (or Spirit Play) work as a method to facilitate support groups in BH: WISDOM STORIES: Studies have shown that stories activate our brains. As soon as we hear a story, our brains naturally want to connect the story to our personal experience. That is why metaphors work. Thus, mythologies with universal spiritual themes/archetypes are fabulous tools to reflect about one’s inner life and struggle. These include stories of our experience of change and transformation: the human journey from darkness to light, from death to resurrection, from being lost to being found, from disorientation to some clarity, from chaos to stillness, from despair to hope, from emptiness to meaning & purpose, from dis-ease towards healing. It gives the person feeling lost and disoriented to map themselves in the endless cycle of ups and downs of life. It gives the person in crisis the mental and emotional space to see the bigger picture, a lens with a much wider perspective, instead of a very narrow, reactive and blind-spot-laden lens to view one's experience. The brilliance behind Godly Play is that instead of the hearer merely imagining the story in the mind, one is also able to touch the story in a tangible way through storytelling objects laid out on the floor. In Montessori understanding of learning, “What the hand does the mind remembers.” One patient responded to the method, which he experienced for the first time, in this manner: “I have heard this parable numerous times in my life, but witnessing this story unfold before me through these objects on the floor allows me to reflect on this story in a different way – a deeper way.” Lastly, wisdom stories allow participants to share their story in a way that's comfortable to them. While some might choose to be vulnerable with the group by sharing the details of the "dark" and "stormy" moments of their life journey, the participant can simply agree and point out that the archetype ("dark storm") was something that they went through.  MUSIC & SONG: Just like storytelling, music activates the brain. Music has the magical power to tap into feelings, thoughts and memories hidden and bubbling underneath one’s consciousness/awareness. A kind of timelessness happens in music. By nature it is affective: organized sound puts us in the pre-verbal or pre-cognitive state of human experience. It helps us remember and reconnect with our sacred past in the present moment. If used wisely, music can be used as a sound to self-regulate: by making a musical sound, one has to breathe; but one can intentionally make a sound or musical tone that is calming, reflective, and meditative. If it is a song with poetic and metaphorical lyrics, it can put the listener in a prayerful and contemplative space. As one patient reminded me: “Singing is like praying twice.”  ART REFLECTION SHEETS: Like music, visual arts also invites us to move our hearts and minds in the affective dimension through color, lines, shapes and symbols. There are things that one can portray in shapes and color that may not be captured through words. This artist and mental health patient talks about how visual art has been an effective tool to express himself.

0 Comments

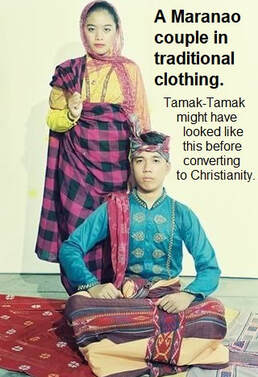

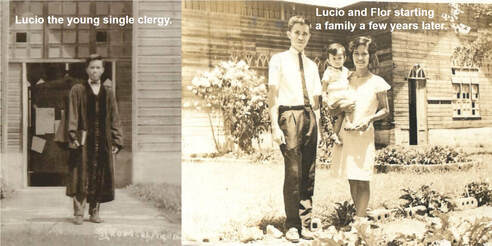

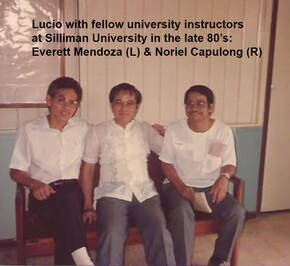

A Sojourner: An Ancestral Trait In 2013, Lucio attended a grand Mutia family reunion in Mindanao. This reunion, however, was different. For the first time, my immediate relatives celebrated with the Muslim side of the Mutia clan. According to Lucio, a Christian Mutia relative and a Muslim Mutia relative crossed paths and struck a conversation about how they are connected in the family lineage. This conversation eventually led to the grand reunion. Our Ancestors The Muslims of the Mutia family are Maranaos, descendants of Shariff Kabungsuan - the first sultan of the south (Footnote: The Maranao tribe - pejoratively known as “Moros” - are infamously known for their resistance towards Western colonization both by Spain and the United States - hence, they remained Muslim. The United States created the 45 handgun because of their fierce battles with the Maranaos). At this reunion, we learned how the Mutias eventually became Christian. During the Spanish times in the mid 1800’s, one ancestor (my great great grandfather) - fondly nicknamed “Tamak-Tamak” - converted from Islam to become a Christian after marrying a Christian woman. We learned that he was a merchant and never stayed in one place. He frequently travelled from town to town and travelled back and forth between Mindanao and Bohol.  So I asked Dad, “So he seemed unable to put down roots and stay in one place. He was a wanderer. Doesn’t that sound like you?” “You’re right,” he nodded in response. Growing up with Lucio as my dad, I always wondered why he could not stay in one place. Part of this of course had to do with his vocation. Clergy work often involves moving from one church to another. His confused older siblings (farmers deeply rooted to their land) shamed him: “We don’t understand your job - you’re constantly moving and you don’t have your own house. We might not have much, but we have dignity: we have our own house and land.” Dad, however, had no retort - he would just smile quietly. He understood their concern, but unlike his brothers who are anchored to the land, he was a sojourner. He was not phobic to novelty. If a new professional opportunity showed up, he would check it out and give it a try.  An Ancestral Mythology of the Stormy Seas Some years ago Dad shared an interesting ancestral story about one of Tamak-Tamak’s sons Eugenio (my great grandfather) and Eugenio’s son Francisco (my grandfather). One of Eugenio’s sources of living, on top of farming the land, was as a fisherman. One day Eugenio told his young son to paddle their only bangka (Filipino double-outrigger dugout canoe) into the deep waters because a massive storm was coming. Francisco didn’t have much time to ask why or protest, and simply did what his father commanded. Soon as he was out in deep waters, giant waves came, and my young grandfather carefully rode the bangka on the crests and troughs of the waves.  When the storm ceased, the young Francisco rowed his boat back to the shore only to see all of the bangkas on the shores destroyed by the giant waves that crashed the shores. I think that this story was a significant story for Lucio about his young father. Now and then he would retell this story to me, but I couldn't quiet understand why this story was meaningful to him until after his death. Lucio's Journey Leaving the Farm to Pursue Education Lucio was born on February 11, 1938 as the youngest of 9 children to a rural farmer and barangay captain (head official of the town) in Bato, Plaridel del Norte in Mindanao. Then at age of 14 young Lucio left the family farm with the adventurous spirit that would characterize his whole life. After quitting a week of work as a kargardor (cargo/baggage handler) at a ship port in Marawi, he found a job as a front desk clerk of a small hotel owned by a well to do Muslim man. This man was enamored by Lucio’s hard work ethic, and subsequently offered to financially sponsor his education and adopt him as his son but with one condition: Lucio must become a Muslim. The generous man even wanted to sponsor his trip to go on a hajj to Mecca. Dad could have easily taken that offer and reclaim back our Muslim ancestry, but he didn’t. Instead, he took an educational opportunity and scholarship at Silliman University’s Divinity school to pursue Christian ministry.  Clergy Work to Full Time Teaching After earning his education at Silliman in the early 60’s he became a young ordained UCCP minister (United Church of Christ in the Philippines) and served churches in Mindanao where he met my mom. In the midst of his church ministry he managed to create space and time to earn a Master of Theology. After his last church ministry in Ozamis City in 1978, he decided to return to Silliman after about 15 years of church ministry to become a full time university instructor at the Philosophy and Religion department. He taught at Silliman for 13 years. This is where I hold most of my childhood memories. During this time, he went to Virginia for a year in 1986 to further his training in Clinical Pastoral Education.  CPE in the U.S. and the Philippines In 1991 he took off once again - this time to take a Clinical Pastoral Education supervisor position at the Medical College of Virginia Hospitals (VCU Hospitals). He also took up church start ministry with the United Church of Christ for the Filipino American community in Richmond, Virginia. Then after 19 years of ministry in the U.S., he decided to return to Silliman to develop a Clinical Pastoral Education program, which is a movement that continues to expand in the Philippines to this day.  Shallow Faith Versus Deep Faith As a natural homebody, I continued to puzzle over Lucio transplanting multiple times in his life and seemingly unintimidated by new frontiers and new opportunities. He seems to travel through new cultural terrains with a genuine sense of joy and adventure. Then I remembered him preaching a sermon at his church in Richmond Virginia that stuck with me. He said that there are different levels of faith. Imagine faith as a kind of exploration of the sea. There is ankle deep faith. This means that you are taking low risk in venturing the waters, but you still feel secure because you are on shallow water. Then there is knee deep faith. The water now is a bit higher and you might be able to feel the current of the water, but you are still in control. Then there is faith that is at the hip level. Here the ground you are walking on might begin to be blurred by the water, and you feel the currents to be a bit more stronger now. But in general you still feel safe. Then there is chest deep faith - here, your sense of safety has diminished. You start to begin losing your balance as the currents have more power over you. And you may no longer be able to see the ground you are walking on. But God, he said, calls us to true faith, which is to let go of the ground under our feet by swimming into deeper waters. True faith means that you allow the currents of the sea to carry you. You are not in control anymore.  Then I am reminded of the story Lucio shared about his dad, the young Francisco, who had to paddle out to the deep waters so that the giant waves would not crush their family’s bangka on the beach. Going out into the sea is deep faith. Then I am reminded of Jesus, as someone who frequently hung out with fishermen was on a boat - Jesus did not find the depths of the sea intimidating especially during a storm. Jesus calls us to explore, not ankle deep, not chest deep - but out into the deep turbulent waters.  God’s Abiding Presence When Lucio was a clergy for Filipino American churches in Virginia, I remembered that certain biblical texts made him reflect introspectively. Psalm 139 was one of those readings. In deep contemplation, he would often close his eyes, and put his prayer hands in front of his lips. 7 Where shall I go from your Spirit? Or where shall I flee from your presence? 8 If I ascend to heaven, you are there! If I make my bed in Sheol, you are there! I believe that this is the text that gave my Dad ease and a sense of security in his new adventures. We cannot escape God’s abiding presence. God is in the here and now, in each step, in each breath, in each moment. With this knowledge, Lucio was able to venture into the depths of the Sea of Life, and allowed himself to be freely carried by its currents. He explored new territories, not with anxiety, or fear, but with curiosity and wonder. On the Wings of Prayers and Songs

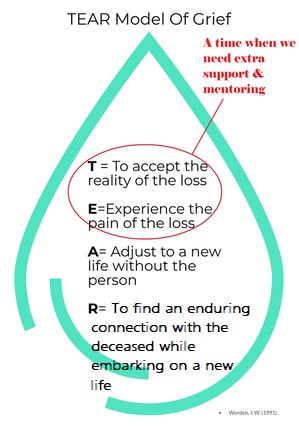

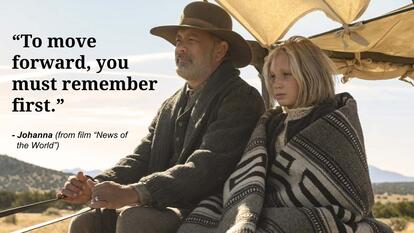

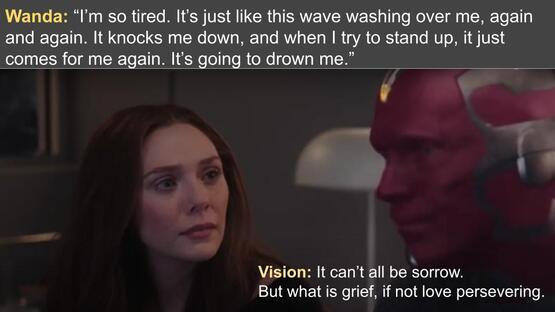

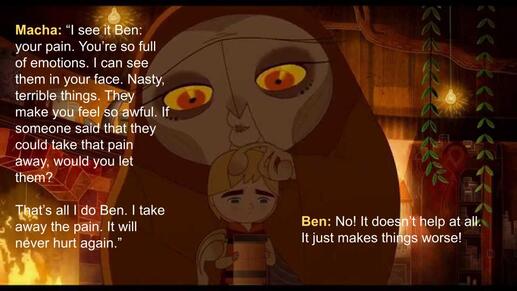

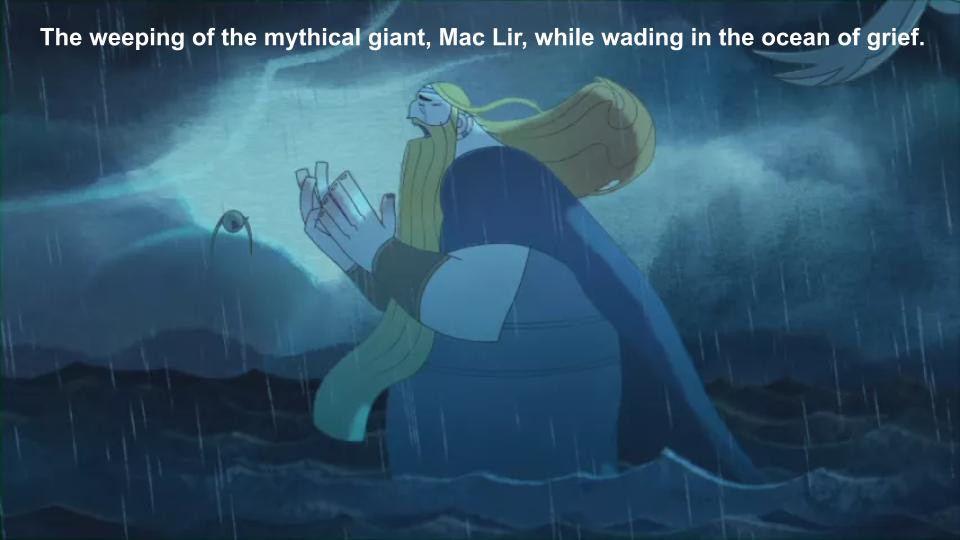

Avoiding retirement upon his return to his homeland in 2010, Lucio worked to develop a Clinical Pastoral Education program in Dumaguete City and beyond, mentoring CPE chaplaincy students and supervising CPE students in supervision track. After ten years of planting the seeds of CPE chaplaincy training programs in the Philippines, Lucio ended on May 2nd the earthly chapter of his life, as he drew his last breath and his spirit embarked on another new adventure, born on the wings of the prayers and songs of the many family members who gathered at his hospital bedside virtually. Lucio’s story of adventure & exploration continues in the stories of the many students he taught, the chaplains and pastors he mentored, the church members he counseled and led, and the family he loved so dearly. His story is now part of our story. May we join Lucio, my dad, our mentor, our teacher, colleague and friend in courageously standing on our faith, as we journey into the deep currents of the Sea of Life. AMEN. An exploration of archetypes in complicated grief through two films: (1) WandaVision, and (2) Song of the Sea. #WandaVisionComplicatedGrief Introduction In the film "News of the World," Jefferson Kyle Kidd helps a young girl Johanna who has had so many losses and traumatic experiences. Kidd assures Johanna that their goal now is to journey forward and make new memories to replace the bad ones. But Johanna retorts: "To move forward you must remember first." Theologian Richard Rohr affirms this insight in his book Breathing Underwater when he writes: “You cannot heal what you do not first acknowledge.” Since, as English author Neil Gaiman points out,  The Challenge: First Two Tasks in Grief In my blog on “Being A Good Host to Our Grief,” I reflected on the second task of grief - which is about experiencing the pain of grief (theorized by William Worden). In grief work, many grief experts phrase this skill as “feeling our feelings” or gently “leaning into our grief.” This work is not easy. There are normal bumps and complications that take place on the grief journey - after all, grief is non-linear. It twists and turns. It is labyrinthine. You take three steps forward, then you take two steps back. It oscillates nonstop between symptoms of loss and symptoms of restoration. However, there are situations when the person journeying through grief may feel stuck. For some it may feel like a nightmare that won't let up. For others it is a long-term feeling of being drowned by one or all of the many common (and normal) grief symptoms: anger, guilt, depression, meaninglessness, denial. When stuckness happens, it is important to reach out to a professional grief counselor for support. It is not recommended to go through grief alone. This is the healthy way to move forward: journeying through it with a companion(s) who know the process, and can witness and validate your experience, and mentor/model for you how to wade the waters of grief.  The Controversy In the grief world, complicated grief is a controversial topic. Some experts consider complicated grief a disorder that must be diagnosed and fixed. Others, on the other hand, believe that this phenomenon is a normal process of grief. Critics of "complicated grief as pathology" perspective claim that it supports misinformed and antiquated notions that (a) grief symptoms are a type of sickness that must be problem-solved, and that (b) there is a grief timeline and a right way to grieve. While the caution of those who critique ideas of complicated grief as a type of pathology is warranted, I also think it is important to note, at a minimum, what causes grief to be complicated - specifically, the experience of being stuck. The root cause goes back to the first two of Worden’s tasks of grief: 1. accepting the reality of the death, and 2. feeling our feelings. (See the illustration of the TEAR Model of Grief above). The tendency to deny reality and avoiding painful feelings is a normal human tendency that we all do at some level. But avoiding these two tasks at all cost - that is, dodging the task of accepting the reality of the loss and feeling the pain of the loss is, I believe, what causes complicated grief. It is OK to be tentative, but we still have to give dipping our toes in the waters of grief a try in spite of our fears and discomforts. Sometimes we may not have a choice: whether we like it or not, the tsunami waves of grief will wash over us anyway and we find ourselves trying our best to keep our heads above water. Whatever the case may be, the skill of learning to be in relationship with the waters of grief (i.e., emotional self-regulation) is crucial. This skill can be learned from others, say, from the loving support of a counselor or therapist. The following films below explore complicated grief. I invite you to view these films to get a sense of complicated grief and its patterns. TASK #1: Wanda's Alternative Reality (WandaVision)Released by Disney Plus, this film tells the story about Wanda Maximoff (from the Avengers) and her unresolved grief, including the death of her loved one, Vision. In this film, Wanda creates an alternate reality, a fantasy land, which keeps her in denial and out of touch with the pain of her many losses. Eventually, she is able to articulate the cause of her hesitation to do the first task of grief, which is to accept the reality of the death of her loved ones. She is terrified of being drowned by her grief. Vision replies with a few words of comfort: “It can’t all be sorrow.” He ends by saying, “But what is grief, if not love persevering.” This conversation is planting a seed of a different perspective in Wanda’s mind, namely, the possibility that “talking about [her grief] would bring [her] comfort.” Wanda learns that in order to move on with her life, she has to dismantle her fantasy world and let go of it in order to be able to do the second task: to feel her grief. TASK #2: On Bottling Emotions (Song of the Sea)Directed & written by Tomm Moore, the beautifully animated story of grief revolves around the family of a lighthouse keeper. After Conor’s wife dies, he avoids the task of feeling his pain. On the anniversary of his wife’s death, he goes to the pub to self-medicate his grief. The belief in avoiding grief at all cost is embodied by Conor’s mom “Granny” and Macha the Witch. To Granny & Macha, venturing into the sea or waters of grief is unsafe. The goal is to prevent those “terrible feelings” from “bubbling up”- one must bottle them up because these “nasty things” are “sick,” can “control you” and make you “feel so awful.” In this view, staying asleep from our pain by hardening our hearts into stone is “peaceful.” When Conor's son Ben realizes Macha's lie that by bottling up one’s pain “it will never hurt again,” he exclaims: “No, it doesn’t help at all. It just makes things worse.” Leaning into our grief is a skill. It is about learning how to swim and wade without fear of being controlled by them, without the fear of drowning (like Wanda). In the end, what liberates Conor's family from feeling trapped is music through the magical shell given by Conor’s wife to her kids. The shell allowed them to sing the song of the sea. They are able to remember her through story and song, giving them the gift of wading and swimming into the waters. CONCLUSION

To close, the characteristics of someone with complicated grief include one or both of the following: (1) The desire to create an alternative reality that is not congruent with the reality of the loss. This human impulse, embodied by Wanda (in WandaVision) goes against Worden's task number one. Complicated grief also includes (2) the belief, held strongly by Conor and Macha (in Song of the Sea), in bottling up one's grief by making feelings and emotions suspect; here, emotions are not safe. This view prevents the griever from doing task number two of Worden's Tasks of Grief. These two actions cause the griever to feel stuck in their grief journey. Thus, getting unstuck requires one (like Wanda) to face one's fear of drowning in the sea of grief, and develop skills to open up oneself to be in relationship with one's feelings (gently leaning into grief) and learn to wade and swim in it.  Occupying oneself with busy-ness is something that many people go through, such as those who are grieving or those who are burned out and going through compassion fatigue. Many want to return to the old norm by going back to work and just get busy. Many will say something like, “You know, I’m keeping myself busy. It really helps.” And it’s true. As a form of distraction, busying does help to some extent. In grief, for example, it is one of the things that we recommend to bereaved individuals especially if their grief is overwhelming. Sometimes we might say, “Do a fun project like gardening, or perhaps do an art work.” Distraction has its place. But unfortunately, we can swing to the extreme with distractions. Instead of creating a balanced approach between feeling our feelings, and getting distracted through something that keeps us busy, we end up using busy-ness as a kind of a drug to numb ourselves from our feelings so that we don’t have to feel anything and become self-aware. Writer, Wendy Mogel, notes the danger of using busy-ness as way to numb ourselves from pain. She writes: "Busy-ness is the manic defense against despair. We speed up our lives unintentionally to escape feeling helpless. We’re not afraid of losing time but of having time to reflect. Without the usual distractions and interference, we may have to confront feelings of disappointment, loneliness, frustration, and our fear that we are not strong enough to make changes we need to make.” So how do we slow down so we can become self-aware? How do we keep our brains from auto-piloting? How can we slow down so that we can take a deep breath and be fully present? How can we slow down so that we can be aware of our conditioned patterns of thinking and doing, so we can make the changes we need to make? There is an ancient spiritual practice that might be a good antidote to busy-ness. And it might help us slow down. This practice involves walking a labyrinth. The labyrinth is an ancient symbol, an archetype. It is a divine imprint, found in all religious traditions in various forms around the world. If you are not familiar with labyrinths, see this video, and this handy guide on how to walk a labyrinth.  A key principle in a labyrinth walk is to be in the present moment in each step that you take. There are 3 stages: (1) Release, (2) Receive, (3) Return. First, as you walk towards the center of the labyrinth, you release your thoughts and worries - anything that keeps you anxious and afraid. Second, when you arrive at the center of the labyrinth, you receive. At the labyrinth’s center, we may bring up these wonderings: What insights have you gained? Perhaps it is something that you have learned about myself; perhaps a feeling of gratitude or a sense of peace; perhaps a deep sense of connection. Third, as you return and walk back out of the labyrinth, the goal is to integrate (or embody) the gift that you have received in your daily living. Adapting the Stages to Your Work with Patients Here’s the cool thing. While it is beneficial to do a meditative walk in a labyrinth, you can still integrate its main principles in your work. When you provide care for a patient, or someone in crisis, we do not have to default busy-ness to pass time with. Instead, we can turn these encounters into opportunities, much like walking a labyrinth. Release On your way to see a patient or their family, let that be an opportunity to release your worries, fears and anxieties. Instead of closing yourself in worry or fear, name your intention, and open your heart.  Receive The second stage in walking a labyrinth is arriving at the center to receive. In your work, the labyrinth’s center is your interaction with your patient (and their family). Here you have the opportunity to receive a gift from this interaction even if that interaction might be challenging. After your interaction with you patient, pause. What insights have you learned about yourself? What does your learning from your interaction mean for your daily living? If any, what changes do you need to make in order to thrive and live more fully? Return The third stage is to return back to your daily living and integrate that insights that you have learned from your interaction.

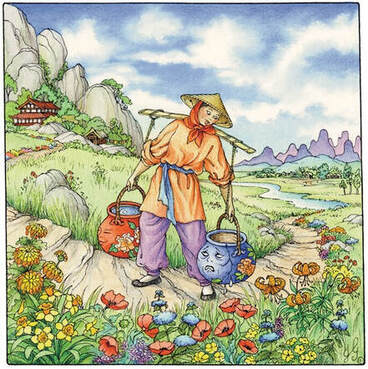

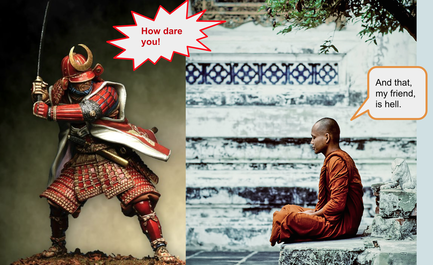

In my previous blog post, I claimed that that part of the reason for why we tell and retell stories about those who have died has to do with the healing act of remembering. By putting up ofrendas in honor of our loved ones and by retelling the story about their lives (just like in the Disney's children's animated movie Coco), we are able to reconnect with them again in the present moment. However, there is also another reason for the significance of why we remember and honor the memory of those who have died. And that is to become a good host to our grief.  There is a phase in the grief process called “disorientation,” which is also known as the “pits.” Disorientation is the most difficult phase to go through because we are disoriented. We feel lost and confused. We are not fully functional the way we used to be. We are mentally unfocused, spacey and tend to forget. Most importantly, this is a period when we experience the very intense painful feelings: deep sadness, or grief bursts, or overwhelming anger, or perhaps incapacitating guilt, or fear.  These painful feelings come knocking on the door of our hearts and minds like uninvited guests. I say they are "uninvited" because we do not necessarily want to feel them. So as the host or the doorkeeper of our hearts and minds, we can either shut them out, and not let them in. We tell these feelings related to our grief: “You all are not welcome here. Go away.” An easy way to shut them out is to busy ourselves. This is normal. By going back to work, and by returning to our regular routines of doing the mundane tasks of our lives, we distract ourselves from these uninvited guests that remind us of the pain of the loss. As a coping tool, ignoring these feelings by busy-ing will work, but only to an extent. As a participant of my grief class said: “Yes, busying works, but only for a while.” In other words, it is a temporary fix. Why? Because by ignoring these feelings, grief does not really go away. In fact, sometimes, the pain of grief gains more strength when we ignore and refuse to name them. No matter how hard we keep grief out of our awareness, somehow grief still manages to come around and return to us like a boomerang and painfully hits us when we least expect it.  So travelling on our grief journey skillfully ultimately means NOT ignoring grief when it comes knocking on our doors. Grieving skillfully means becoming good hosts by letting them in and recognizing them. Yes, these painful feelings can be intimidating - but if we take a few deep breaths (take a couple now), and just notice. Notice where our grief stays in our bodies - perhaps it come as a kind of tightening of our chest, perhaps an achey neck and shoulders, or a churning stomach, or as an intense migraine. The amazing thing is that when we let ourselves become good hosts by staying in the present moment and closely observe how grief works in our mind and body, their power and grip over us lessen and shrink. We eventually learn that these feelings really have no real terror in them. They’re just . . . feelings.  And that’s why we remember and retell the memory of our loved ones. We do it to keep the doors of our hearts open and to become welcoming hosts to our grief. By sharing a sacred story or memory about our loved one, we honor our grief who is our guest. And our grief will not stay with us forever. Grief is not a freeloader asking for free rent space in our hearts and minds. Grief will eventually leave. And yet, neither will it go away a hundred percent. Grief will always come back knocking for a visit, even many years from now. But each time grief comes for a visit, our relationship with it deepens, and it becomes an old friend and a source of wisdom. As we enter deep into the spirit of Christmas and into the darkness of winter, we celebrate how hope and new life emerged out of peasant town called Bethlehem during one of the most violent times of Roman rule in Israel. New life comes out of unexpected places, sometimes in spaces might perceive as insignificant and not worthy of attention.  The Parable of the Broken Jar Once upon a time, there were two water jars used by a peasant to draw water from a well to his house. One jar was perfectly new, while the other one was old and cracked. The jars hung on opposite sides of a pole that the owner put over his shoulders. The old jar was feeling depressed and sorry for itself for being old, worn and having a crack. So one day, it spoke to the owner: "I'm sorry for all of your hard work you are doing each day to bring water to your family. However, I continue to be unhelpful and useless. Because of my crack, I spill the water that you carry from the well to your house." The owner replies: "Tomorrow when we get water from the well and walk back to the house, I want you to look at your side of the path, and notice what you see." So on the way back from the well, the old jar did the usual spilling of its water on the path. But the owner reminded him: "See on your side of the path? It is filled with beautiful flowers. I always knew about your crack, so I threw flower seeds on your side. And because of the water that you've spilled, the seeds have grown into flowering plants. I have picked these flowers, placed them in a vase in our house for my family to enjoy. So if it were not for your crack, how could my family have benefited from the flowers that you have provided all these months?"  Perfectionism & Busy-ness Brene Brown says that riding through life driven by perfectionism is not a fun ride: "When perfectionism is driving us, shame is riding shotgun and fear is that annoying backseat driver." Perfectionism conditions us to be ashamed of our cracks. We learn to ignore them not by slowing down, but by speeding up through our busy lives. While slowing down to rest might be what is needed, the act of slowing down can can threaten the mask of perfectionism. Slowing down unveils it. In my work in bereavement, many of bereaved individuals will automatically default to busying themselves as a form of distraction from confronting feelings that accompany the loss of their loved ones. Running away from feelings of grief works only for a while. A grieving daughter told me, “For a while for many months I was OK. I went back to work, back to my regular routine. Then for some reason, my grief came out of nowhere. I was in a baseball game with my husband, everyone was cheering, happy and celebrating. And there, in the middle of the party, I was overcome with an explosion of grief and sobs over the death of my dad.” Just because the emotional injury caused by life's crisis is not outwardly visible, we assume it is in a totally different category from physical injury and that we can simply ignore our grief and go back to "normal" - the way it used to be. Ignoring one's grief may be likened to someone throwing away a boomerang, hoping that it will never come back, but then grief whacks us in the back of our heads when we least expect it. Slowing Down & Going Home If we find auto-piloting in our usual routines after a surgery ill-advised, so it is with emotional injuries. Healing is never about speeding our way back to our regular routines. A good healer will tell us to slow down so our bodies recuperate. Such person will tell us to pay attention to avoid reinjury. When we are injured by the violent tremors of significant life transitions (grief caused by death, health change, mid-life crisis, divorce, economic instability), the best way to heal is to slow down. Thich Nhat Hanh says it well:  Facing uncomfortable feelings (sadness, despair, anger, fear, anxiety) can be very intimidating especially in a culture that recognizes such feelings are impractical and a waste of time. However, the mystic poet Jellaludin Rumi invites us to meet our feelings head on. To him, this skillset of befriending our emotions as sort of like being a host to a guest that has come to knock on our doors. We need to welcome them and let them in.  The skillset that Jellaludin Rumi invites us to embody is easier said than done especially in a culture that considers the expression of feelings as a sign of weakness. Often I encounter many bereaved clients who find their feelings of grief shameful. This is especially true for men who are conditioned to keep their feelings hidden to present a fake persona of resilience.  Shame Researcher on resilience, Brene Brown, talks about shame as a shackle that keeps us from claiming our power. She explains that if you put shame in a petri dish, it needs three ingredients to grow exponentially: secrecy, silence and judgement. In JK Rowling's Harry Potter, the Dark Lord is powerful by the fact that he is the one who must not be named. Shame's default is to sweep difficult thoughts and bad feelings under the rug. Keeping things unnamed and invisible is how shame keeps its powerful grip on us, paralyzing us from claiming that we are strong enough make changes we need to make. But no matter how much we keep shame out of our awareness, it always comes back to return and haunt us. Christian tradition has an antidote to shame: confession (or penance). When the dark and shameful parts of ourselves are being witnessed without judgment by an empathetic listener, shame's powerful grip loses strength. Fully accepted and held in love, the parts of ourselves that are cracked and jagged gets to be seen in a different light. We are perfect in our imperfection and begin to hear the truth when God says: "You are my beloved child with whom I am well pleased" (Mark 1:11). New Life  With this affirmation, new life happens. But new life is not comfortably fuzzy, cute, spiffy, clean-cut, frangrant or crystal clear. New can be messy and at times confusing. New life comes from out of the stench of the dark tomb. New life emerges out of the dirt. Decaying compost and mulch nourishes the seeds and the growing plant in the spring.  In the end of the Story of the Cracked Pot, the cracked pot was eventually able to claim the beauty of its imperfection. In the art of Japanese pottery called Kintsugi, broken bowles are repaired with gold. The flaw is seen as a unique piece of the object's history, which adds to its beauty. Thus kintsugi is the art of precious scars. As we live with our prescious scars and inner cracks, may we find hope in our journeys. May we have the eyes to see the emerging of new life and beginnings in the dark crevices of our human experience.

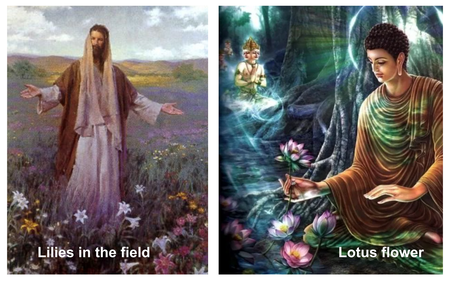

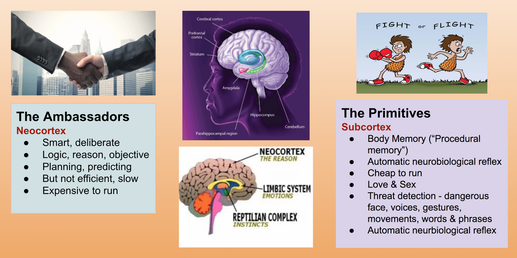

After 28 years of living in the northern hemisphere, my tropical genes still do not welcome the arrival of cold air of fall. However, my eyes welcome the vibrancy of the colors that come with the change: the bright yellows, reds, and oranges on the trees. My neighbors and my family put pumkins on our porches. I dug a hole and buried my tulip bulbs for the spring. The beautiful zinnias in my front yard finally succumbed to the cold, lost their colors, and readied themselves to return back to the earth. I am thankful for the fall season's reminder that nothing is permanent. Impermanence in Sports  I learned the spiritual practice of impermanence through athletics, specifically, Brazilian Jiu Jitsu. In martial arts, rigidity of form will get in the way of your performance. When I roll with my training partners on the mat, my coaches encourage me to move fluidly with impermanence as best I can by adapting my movement to my training partner's movement. I often hear them invite me not to let my fight-flight brain to take over, which slows the practitioner's progress. In a fear-based fight-flight approach, my muscles are stiff, my heart is racing fast, my breathing shallow, certain muscles that do not need to be activated are in full tension. My physical actions are not well thought out. I get tired fast, more prone to injury, and I'm not having fun. Instead, I hear my coaches telling me to relax, to slow and deepen my breathing, and pay full attention to what my body is doing in relationship to my training partner's movements. They invite me to not focus on the end result (winning or losing), but pay attention to the present and have a good sense of fun and play. (For a more comprehensive discussion on this topic, read Matt Thornton's blog "Mindfulness & Martial Arts.") As the late martial arts philosopher Bruce Lee puts it: Empty your mind. Be formless, shapeless, like water. If you put water into a cup, it becomes the cup. You put it in a teapot, it becomes a teapot. Now water can flow, or it can crash. Be water my friend." On Life & Music by Alan Watts Eastern philosopher Alan Watts also makes the value of non-attachment clear when he reflected on "Life and Music":  "In music, one doesn’t make the end of the composition the point of the composition. If that were so, the best conductors would be those who played fastest, and there would be composers who wrote only finales. People would go to concerts just to hear one crashing chord — because that’s the end! But we don’t see that as something brought by our education into our everyday conduct. We’ve got a system of schooling that gives a completely different impression. It’s all graded and what we do is we put the child into the corridor of this grade system, with a kind of, “Come on kitty kitty kitty!” and now you go to kindergarten, you know, and that’s a great thing because when you finish that you’ll get into first grade. And then — Come on! — first grade leads to second grade, and so on, and then you get out of grade school. You go to high school and it’s revving up — The thing is coming! — then you’re gonna go to college, and by jove, then you get into graduate school, and when you’re through with graduate school you go out and join the world. Then you get into some racket where you’re selling insurance, and they’ve got that quota to make and you’re gonna make that, and all the time “the thing” is coming — It’s coming, it’s coming! — that great thing: the success you’re working for. Then when you wake up one day, about 40 years old, you say, “My God, I’ve arrived! I’m there!” And you don’t feel very different from what you always felt. And there’s a slight let down because you feel there was a hoax. And there was a hoax. A dreadful hoax. They made you miss everything. We thought of life by analogy with a journey, with a pilgrimage, which had a serious purpose at the end, and the thing was to get to that end: success, or whatever it is, or maybe heaven after you’re dead. But we missed the point the whole way along. It was a musical thing — and you were supposed to sing, or dance, while the music was being played." Empire Affective Disorder In this reflection, Alan Watts critiques western society's obsession with the trophy of success. But mystics like Watts know too well that such things are illusions, much like a person dying of thirst walking desperately towards mirages in a dessert. Hence, the early Christians were wary of religion when it mixed with the values of the state. Soon after Emperor Constantine declared Christianity as the religion of the Roman empire, the desert monastic movement grew as they moved from urban areas to the wilderness of the desert. In her book, The Forgotten Desert Mothers, Laura Swan discusses how Christians felt a "conflict between the growing power associated with the institutionalization of the church and the pursuit of holiness," and that Christianity was compromised (for example, many conversions to Christianity was for political expediency to access power). A central reason for this conflict, I believe, is that the Christian mystics understood that the values of the empire and the values of the Spirit are antithetical to each other. Grounded on fear and anxiety of fight-flight model of living, the empire is hooked on power, control, permanence. These are the values that Jesus rejected when the demon visited him in the desert to tempt him, namely, the power to transform anything for one's self-centered needs, political control through ownership of kingdoms, and immortality. Theologian, Lynice Pinkard, states that this particular spiritual illness may be called empire affective disorder and its symptoms are fear and anxiety. To self-medicate, those with empire affective disorder use a powerful drug - a mix of a toxic brew of lust for material things (consumerism), superficial blind nationalism, and violence. I believe that this toxic brew can result in two self-destructive ways of being in the human spirit: 1. Nihilism - aka meaninglessness, which is inward driven (implosion of self-destruction). 2. Narcissism - self-centeredness on steroids - which is outward driven (explosion of violence towards others). Spiritual Practice of Apatheia To rebel against the values of the empire, the Desert Mothers took Jesus' invitation seriously through their monastic spiritual practice of apatheia: an antidote to spiritual illness caused by empire affective disorder. In Laura Swan's book, The Forgotten Desert Mothers, apatheia is the: “interior spiritual journey (mature mindfulness) in which the inner struggle against inordinate attachments has ceased, and one is free of pulls from worldly desires, attachments to ego, self-imposed perfectionism.” The desert monastics used the wilderness of the desert to achieve this goal. To mystics nature is a stepping stone to disentangle oneself from the shackles of the ego.  Flowers & Nature One reason for this is that in the vastness of nature, the human self is insignificant and ceases to be the center. Nature's transitoriness and ever-changing quality make the illusion of permanence more clear. We experience "oneness" with the beauty of nature in the present. To Jesus, this is where God's kingdom resides - not in the faraway future, but in the eternal now. Jesus says: "“Consider the ravens: They do not sow or reap, they have no storeroom or barn; yet God feeds them.” And “Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow; they neither toil nor spin, yet I tell you, even Solomon in all his glory was not clothed like one of these.” The Buddha shared a similar insight using a flower. As the disciples of the Buddha sat around him in a small circle by a quiet pond to wait for his teaching, the Buddha simply pulled out a lotus flower and silently held it before them. These two mystics, Jesus and the Buddha, invite us to observe the ways of creation. In nature, nothing is permanent, but beauty, abundance, and grace overflows. As we move together with impermanence in the fall season, let us take a deep breath, be present in our bodies, and sing and dance while the music is played.  The synoptic gospels tell the story of very scared and anxious disciples on the boat pounded by a storm. After the disciples express their fear of drowning, Jesus says, “Peace be still,” then calms the seas. He invites them to have faith and not be afraid. In the middle of the stormy seas, Jesus found peace and invites his disciples to do so. Likewise, the Buddha invites his followers to find stillness in the eye of the storm (samsara) amidst our chronic and vain attachment to things shallow, superficial, impermanent and ever-changing. We seek deep peace in our lives and yet our instincts to hook on to our anxiety, worry, anger, and fear seem to constantly follow us wherever we go. Its ugly head rears itself without warning. We wish we have control over our anxiety and fears, but our automatic threat response system seem to be a bit more wiley than we wish it to be. And before we are even aware of it, the automatic threat response system has taken over the driver’s seat. The Subcortex  In his book, Wired for Love, couples therapist Stan Tatkin talks in detail the researched data from neuroscience about the dynamic between the brain’s prefrontal cortex and the subcortex. He calls the former, the “ambassadors” - the part of our brain that specializes rational thinking. He calls the latter “the primitives” - which is the home of our automatic threat response system. In general, our brains lean towards negative bias (1 to 5 ratio of positive to negative), it has an extremely efficient tracking system for potential threats. The amygdala in our subcortex for instance exists to do what it was designed to do over thousands and thousands of years - to help us survive from life-threatening attacks from predators. In a way, we literally have a kind of a reptilian instinct within us. This is our dragon. This raw animal instinct in us has come up in our mythology, our sacred stories, usually in the form of an actual animal (snake) or a giant reptile with wings that breaths fire (dragon), or someone that is part human and part animal (centaur, minataur). Or perhaps a human figure with horns of a ram with bat-like wings (devil)? Mythology Our human struggle with the dragon within ourselves is well recorded in human mythology. Scholar of mythology Joseph Campbell explains that the dragon from the East and the dragon from the West have differences. Personified in the story of St. Michael and the dragon, the western dragon, Campbell says, is to be killed so that the hero(ine) can access the treasure that the dragon protected in its lair. The dragon represents our ego, and our attachment to it. In western mythology, the ego has to die in order for resurrection to a life that is free from the shackles of self-centeredness.  The eastern dragon, on the other hand, is different from its western counterpart. The Chinese dragon, for instance, is not necessarily an enemy to be defeated and killed. This dragon however is still dangerous and wild, much like it’s western equivalent. But this dragon represents vitality - it dances, it beats its chest and laughs a big belly laugh. This dragon invites the hero(ine) to participate in the dragon dance. A few times in San Francisco’s Chinatown, I have seen youth who take Chinese martial arts, take on the dragon costume to do the dragon dance. Below are some mythologies - both contemporary pop culture and ancient - on the human struggle to tame the dragon within. Bruce Lee, the Dragon Fans of Chinese Kung Fu films know that Bruce Lee, the martial arts hero, is identified as the dragon. He was an athlete who immersed himself in eastern philosophy which he integrated in his physical discipline. Lee fully understood that in order to become an adept athlete (which in his case is as a martial artist), he had to be aware that ultimately the demon that he has to fight with is not his opponent in front of him. The demon (the dragon) is within oneself: the attachment to one's thoughts and ego, unable to see "what is" in the here and now. In this clip from the blockbuster film Enter the Dragon, Lee engages a philosophical conversation with an old and wise shaolin monk about the value of engaging the martial arts discipline without the interference of the ego.  The Ancient One (in Marvel's Dr. Strange) The Marvel film, Dr. Strange, also highlights the eastern mythology of the dragon within ourselves through a conversation between the master (the Ancient One) and the student (Karl Mordo). Karl Mordo (disciple): “I wanted the power to defeat my enemies. You gave me the power to defeat my demons." Ancient One (master): “We never lose our demons, Mordo. We learn to live above them.” The Ancient One points out to the student (Karl Mordo) that overcoming the one’s demon does not mean eliminating (or losing) it for it is an inextricable part of who we are, so much so that we are hardly aware of it when it acts out through it's lighting speed automatic threat response, or when it narcissistically pumps itself up by stubbornly defending its self-righteousness. Learning to live "above them" is a skill. Stan Tatkin explains that observing our demon-dragon (our primitives) in action helps to keep them in check. By developing disciplined self-awareness, we can observe how they behave, and begin experimenting if we can catch them in the act. We can develop and refine this skill over a lifetime - but not without help.  The Samurai and the Monk (plus Yoda) For this reason, having a mentor or teacher is part of Eastern spiritual traditions as illustrated in the stories from Enter the Dragon and Dr. Strange. The Zen story about the samurai and the monk focuses on the role of the teacher as the one who guides the student to "awaken" from the self-centered habitual thought patterns of the ego. After a warrior returning home from war crosses paths with a wise meditating monk, the warrior asks the monk: “Explain to me the truth about heaven and hell.” The monk tells the samurai that this was not possible since the warrior was “dumb and ugly.” With his anger triggered, the samurai drew his sword ready to chop the head of the monk. Then the monk says, “And that my dear friend is hell.” The samurai awakens to the teaching of the wise monk. With the insight he had gained, he lays down his sword, and bows to the monk in deep gratitude. The monk then says, “And that my friend is heaven.” In this story, the monk helped the samurai catch his dragon in the act by inviting him to become the awareness or observer of his reaction which was in the process of turning from a small spark into a violent explosion.  The monk taught the samurai awareness of his dragon by poking the samurai's fragile ego. It's very likely that in his earlier life he was bullied and called dumb and ugly. While he might have been an accomplished and respected samurai, he carries with him unhealed inner scars from his past, and continues to suffer each time his unhealed scar is touched. A common wisdom in psychology states that anger at its deepest level is rooted in fear. Anger is a powerful energy that can be utilized to address injustice when our human rights are disregarded. But if we hold on to it like a barnacle, it has the potential to harm us. A small spark mixed with very volatile fuel of hate can cause death and destruction. The Jedi Master Yoda from the Star Wars mythology holds this assumption when he reminds the young padawan: "Fear is the path to the dark side. Fear leads to anger. Anger leads to hate. Hate leads to suffering." In Star Wars, the young Anakin Skywalker succumbs to his dragon and becomes Darth Vader.  Avatar the Last Airbender In the episode entitled “Firebending Masters” of the anime series Avatar the Last Airbender, the two characters Aang and Zuko give us some ideas how not to be paralyzed by our fears. When both confront the two ancient dragons to learn the secrets of firebending, the audience is held for a few moments of the possibility of the two teens being eaten by the dragons. While facing danger, Aang realize that in order to build rapport with the dragons, he and Zuko have to do the dragon dance. As soon as both perform the dance, the wild dragons dance with them harmoniously and gracefully, an act which imbue the two students with the wisdom and beauty of firebending. Both discover that learning the nature of fire merely through one's anger is not enough to sustain healthy resilience in the long-term. Anger - the fire that destroys - has a short life. In the end, they learn the life-giving nature of fire (sun), which sustains life on earth.  Sun-Girl & Dragon-Prince (Armenian Mythology) While stories of humans taming dragons dominates in Eastern mythology, this archetype takes place in Western mythology as well. In an Armenian story, "Sun-Girl and Dragon-Prince," a girl by the name of Arevhat is about to be fed to the Dragon-Prince, but instead of being overcome by fear, she greets him warmly, "Good evening, King's son." The dragon is moved by her presence and empathy that the tears that roll from his eyes melt the scales in his body tranforming him into a full human. Much like the Zen story of the monk and the samurai, this story illustrates how awareness, presence and empathy has the power to tame the violent dragon impulse within ourselves.  Eustace Scrubb Becomes A Dragon (Chronicles of Narnia) In C.S. Lewis' "Voyage of the Dawn Treader," eleven year old Eustace Scrubb begins as an arrogant self-absorbed boy, until he, unbenownst to him, becomes a dragon while on an adventure with his cousins. At some point, he realizes that the dragon that he sees in the pool is his own reflection. He begins to see something about himself that he has not been fully aware before: his "greedy dragonish thoughts in his heart." As a dragon, he tries to embody new behaviors by helping his fellow travellers find food and shelter. Eventually, the great lion Aslan helps him peel off his dragon skin and throws him into a body of water. When he emerges he becomes himself again, but is also transformed into new person that others around him can truly befriend. In order for Eustance to free himself from his dragon tendencies and impulses, he has to fully accept that the dragon is a part of who he is and find some self-awareness of the ways of the dragon. Only then can he allow space within himself to embody kindness, compassion, and true friendship with others. Where the Wild Things Are  Author and illustrator of children's books, Maurice Sendak, also plays with the theme of taming monsters. In the Wild Things Are, Max confronts his monsters as they "roared their terrible roars and gnashed their terrible teeth and rolled their terrible eyes and showed their terrible claws." With the magic trick, he tames them and dances with them. This story points at the notion that often that which we perceive as threatening is often not as dangerous as we think it is. Writer of children’s books, Kathy Hoopman, writes in All Birds Have Anxiety: “The amazing thing is when you force yourself to face what scares you, or you start whatever it is you are worried about, the scariness shrinks….Then you will find that the things you thought would be terrible have no real terror in them, and things you thought would be horrible are not full of horror.”

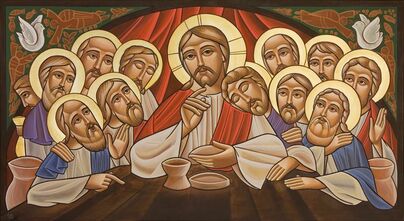

Jesus' Temptation In the synoptic gospels, Jesus struggles with his dragon, which comes to visit him in the form of devil in the temptation scene in the wilderness. The devil offers him the values of self-centeredness: power (turning stone to bread), control (kingdoms) and permanence (avoid death). Jesus rejects these offers when devil visits him in the desert. Jesus overcomes his automatic threat response system by responding to God's call towards altruism, love and empathy. In closing, increasing our self-awareness will help make the dragon within us become more visible. Learning to tame and dance with our dragons is something we can develop and refine, but this will not happen overnight. It is a learning process that will take place over a lifetime, and not without help.  Being lost and not having solid ground under our feet, can be make us feel frustrated, angry and scared. Last August, I flew to Paris to meet up with my wife Sylvia who was in a conference for a week in the UK. Upon arriving in Paris, at first I felt a sense of familiarity. Like the San Francisco bay area (where I lived for 17 yrs), Paris felt very ethnically diverse. I crossed paths with two friendly French people who spoke some English: first a young university student with a girlfriend who helped me read the subway map. The second was a friendly older French lady on the train who told me that Koreatown wasn’t too far away. In the end of our chitchat, she said, “Welcome to Paris. I hope you have a great time here.” This is going to be a great trip, I thought to myself. I was supposed to meet Sylvia at an Airbnb in the Koreatown section of Paris. When I got off from the subway to the streets of Koreatown, it was dark - about 10:30 pm. I whipped out the map I had printed out of google, and started looking for “29 Rue de Belleville,” but then discovered there were no street signs (the next day I learned that Parisian street signs are plastered on the buildings - it’s a European thing). I problem solved this issue creatively: as a visual learner, I used the street shapes and patterns in the printed google map to guide me to my destination. It took a few explorations and turnarounds, but eventually I got to the Airbnb location. It was an apartment building in the middle of a neighborhood replete with Asian grocery stores (a mix of Vietnamese, Chinese and Korean). I stood on the sidewalk exhausted, thirsty and hungry, but Sylvia was nowhere to be found. The apartment gate was locked. I double checked the address three more times. I asked a young French guy who just parked his motorbike in sign language and naming the street just to make sure, and got a clear “Oui”. Still no Sylvia. Forty minutes passed I started to regress. “How can she do this to me? She knows I don’t speak French. Do I really have to stay in the streets for the night?” Feeling desperate, I looked at restaurant across the street and gathered up the courage to ask the young pretty waitress to see if she speaks enough English to help. She said “Non.” I was about to throw in the towel and surrender to the possibility that I might become a homeless person in Paris. But she spoke to her boss, an older lady in her 50’s. Her boss then made an announcement to the few late night customers seated at the table of the restaurant on the sidewalk to inquire if anyone spoke English. A young woman who spoke a little English raised her hand. Geez Louise - finally! She had a kind face. I tried my best to make myself look as desperate as possible. I explained and pointed across the street that my wife is in an Airbnb in that building, but there is no way for me to communicate with her. (I had not set up my cell phone for calls in international travel). At first, she had the look of resignation. All of a sudden her face lit up and said, “Do you want to use my phone?” I said, “I don’t have her building’s phone number.” I felt defeated once more. Then I said, “Do you have Facebook on your phone?” “Oui”, she replied. It took about three attempts of FB messaging, before Sylvia replied. Then she came out of the building to meet me. I scolded her, but I was glad to find her at last. I hated feeling disoriented, disconnected and lost. However, because life is transient and ever-changing, I understand that I am guaranteed to feel these feelings again in my life journey. In travelling, it’s a bit of a cliche when we say, “It’s not just about the destination, but it’s about the journey.” Flexibility is the key here. While we might have a map, we (sometimes) need to let go of the map. It’s a tough challenge: to be present in the here and now moment and deal with “what is”, instead of holding on to our premeditated plans like a stubborn barnacle. Indeed, egoic desire and attachment causes suffering. There is wisdom in going with the flow (thus sayeth the California hippie). It took asking three non-English speaking people before I found my guardian angel that night. I once heard an ancestral story told by my dad that took place sometime during the turn of the century. My great grandfather Eugenio - a fisherman and farmer in Mindanao, southern Philippines - ordered my young grandfather Francisco (or Isko) to take their one bangka out into the deep sea in the midst of a fast approaching storm. My young grandfather Isko thought that his “tatay” (father) had gone mad, but at that moment it was not for him to question him, for there was no time to explain. As Isko rowed his bangka out to deeper waters, he noticed that the waves were getting bigger and stronger. He rode on the giant waves for about an hour until the storm ceased. When he rowed back to the beach, he saw that the other bangkas on the beaches were crushed by the ginormous waves that slammed against the shoreline. Here’s the cud that needs some chewing. There is a way in which utter dependence on hard solid ground is not what we need at certain times of our lives. Sometimes as scary as it may be, we need to go out to the deep even without knowing exactly why, and ride the crest and trough of stormy waves. May we gain the courage to do so.  Eucharistic Remembering or Anamnesis (Coptic Icon of the Last Supper) Eucharistic Remembering or Anamnesis (Coptic Icon of the Last Supper) Over a year ago, my kids and I went to see the new children’s animated movie entitled “Coco” - which is produced by Pixar Films. The visually colorful children’s animation looks into the Mexican celebration of Dia de los Muertos. The story explores the mythology of why we sing songs and remember the dead through an ofrenda - the beautiful altars filled with decorations and pictures of those who have died. If you haven’t yet seen the movie “Coco”, I won’t spoil it for you by giving you the plot of the story. But I will share with you the big idea around the significance of the act of remembering. The premise of the celebration of Dia de los Muertos is that our loved ones never really leave us so long as we remember them. By telling and re-telling their life’s story, we invite them back into our lives. There is an ancient Greek word for that - “Anamnesis” - which is when the future and past coalesce and break into the present moment. So in the act of remembering or “anamnesis,” the retelling of stories about our loved ones who have died allows our loved ones to become present in the here and now. In turn this retelling gives new meaning and new life to emptiness and meaninglessness. Hence, the act of remembering is a sacred act - it is a healing act. Our hearts may be broken, but we fill the open spaces of our broken heart with the healing balm of the memories and sacred stories that we share with each other. That is why we retell our stories: to remember, to reconnect, and embark on a grief journey towards healing. And so, as illustrated in the movie, “Coco” - may we all travel on our grief journey with the goal of being able to sing again. Perhaps not just sing, but also dance again...even if - as the writer Ann Lammot says - even if we dance with a limp. May it be so. |

Donnel Miller-MutiaJoin me in chewing the cud on mindful communication and relationships, self-awareness, spirituality and mythology. Archives

March 2024

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed